To the extent that historical press releases reference BMW Manufacturing Co., LLC as the manufacturer of certain X model vehicles, the referenced vehicles are manufactured in South Carolina with a combination of U.S. origin and imported parts and components.

PressClub USA · Article.

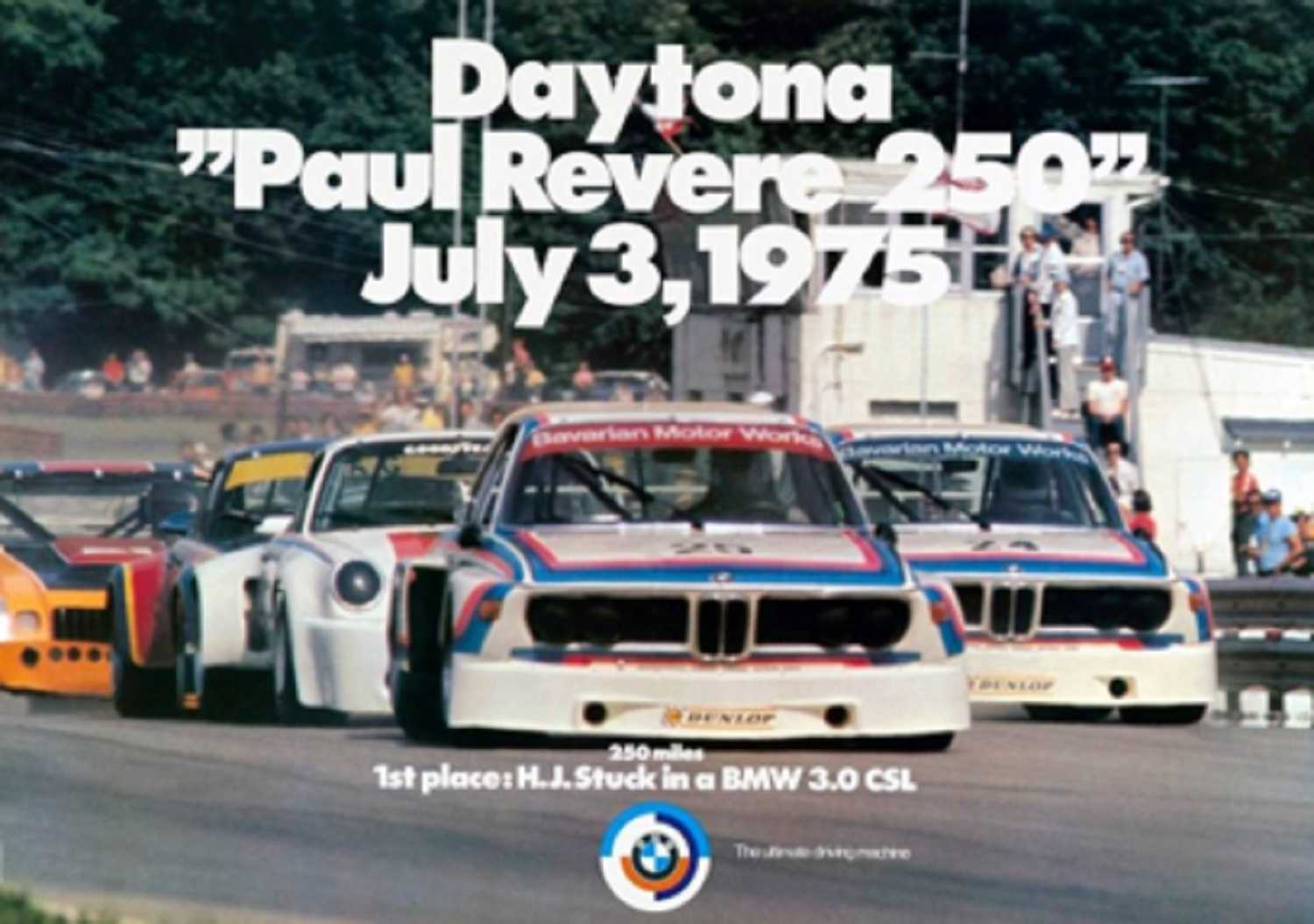

BMW NA 50th Anniversary | 50 Stories for 50 Years Chapter 5: “BMW Motorsport and the Mighty CSL Win The 1975 12 Hours of Sebring.

Mon Feb 03 19:50:00 CET 2025 Press Release

If you’re an automotive executive in charge of sales and marketing, how do you raise the company’s profile when you’re unable to advertise? That’s the situation faced by Bob Lutz in 1974, when he was attempting to replace Max Hoffman’s independent US distributorship with a wholly-owned sales subsidiary. Lawsuits were pending, but until the matter could be settled Hoffman had the exclusive rights to advertise and sell BMW cars in the US. Nothing in Hoffman’s contract would prevent BMW from racing in the US, however, or from advertising its success on the

Press Contact.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Tel: +1-201-307-3701

send an e-mail

Author.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Downloads.

Related Links.

If you’re an automotive executive in charge of sales and marketing, how do you raise the company’s profile when you’re unable to advertise? That’s the situation faced by Bob Lutz in 1974, when he was attempting to replace Max Hoffman’s independent US distributorship with a wholly-owned sales subsidiary. Lawsuits were pending, but until the matter could be settled Hoffman had the exclusive rights to advertise and sell BMW cars in the US. Nothing in Hoffman’s contract would prevent BMW from racing in the US, however, or from advertising its success on the track.

Lutz was a firm believer in racing’s value as a marketing tool, which Porsche had been exploiting for years. “Back in those days, Porsche had zero advertising budget, yet they had a premium image and rising sales both in the US and Europe,” Lutz said. “Porsche notoriety or brand awareness was entirely based on factory participation in motorsport.”

BMW had an impeccable racing heritage dating to the 1920s, but the company wasn’t racing at all when Lutz joined its board of directors at the beginning of 1972. Teams like Alpina and Schnitzer were winning races with the 2002 and 2800 CS, but BMW wasn’t gleaning any marketing value at all from the success of its cars.

Lutz convinced his fellow board members to approve a renewed racing effort, and BMW Motorsport was incorporated on May 24, 1972. Led by Jochen Neerpasch, the team made its high-profile debut in the 1973 European Touring Car Championship.

Alpina had developed a lightweight version of BMW’s big coupe, but didn’t have the capacity to build the 1,000 units needed for Group 2 homologation. Lutz made sure the 3.0 CSL got built, and the lighter, more potent race car took to the track against the works Ford Capri and Porsche Carrera RSR.

Alpina started the season with two wins, and BMW Motorsport followed with four more. In BMW Motorsport’s first year of racing, BMW won the ETCC manufacturer’s title, while Alpina’s Toine Hezemans took the driver’s trophy.

“For me, the 1973 season was probably the best season ever in touring cars,” Neerpasch said. “But we could not continue at this high level because in 1974 the energy crisis started in Europe. It was counterproductive for a car manufacturer to win races at that time. We had to look for alternatives, and we found them in the US. BMW was taking over from Maxie Hoffman, and that was the reason why we came here [to the USA].”

Lutz left BMW for Ford of Europe at the end of July 1974, but his successor Hans-Erdmann Schönbeck carried the plan forward. While BMW’s legal team was working to extricate the US market from Max Hoffman’s grip, its racing team was developing the 3.0 CSL into the 435-horsepower Group 4 “Batmobile” that would take on Porsche in the International Motor Sport Association’s (IMSA) hypercompetitive GT class in North America.

Neerpasch and his “cowboys”—development engineers Martin Braungart and Rainer Bratenstein, six technicians, and driver Hans-Joachim Stuck—set up shop in Hueytown, Alabama, in space rented from Bobby Allison’s NASCAR team. There, they prepared a pair of CSLs for the first race of the 1975 IMSA season at Daytona, emblazoning Bavarian Motor Works across the top of each windshield to dispel the widespread assumption that BMW stood for “British Motor Works.”

Both CSLs would expire before the Daytona 24 was in the books, but BMW Motorsport made a positive impression with its tricolor livery and underdog image against the Porsches. “I think we made friends,” Neerpasch said with a smile. “We had the feeling that people at the races liked what we did, and became fans.”

People also liked Neerpasch’s international quartet of drivers: the German Hans Stuck, Englishman Brian Redman, Swede Ronny Petersen, and American Sam Posey. “They were all terrific,” said Carla Harman, an early employee at BMW of North America who became the team’s PR representative.

Stuck, especially, became a fan favorite, for his tail-out driving style and exuberant personality. “He’s always laughing, and he appears to drive for the sheer joy of it rather than out of some dark necessity,” said Posey. “And then there’s the yodel!” Indeed, Stuck’s yodeling would soon become a regular feature on IMSA podiums, starting at the very next race.

On March 15, 1975, BMW’s lawsuit with Hoffman was finally settled. A week later, BMW Motorsport arrived at Sebring for the second race of the IMSA season, and its first representing the new BMW of North America.

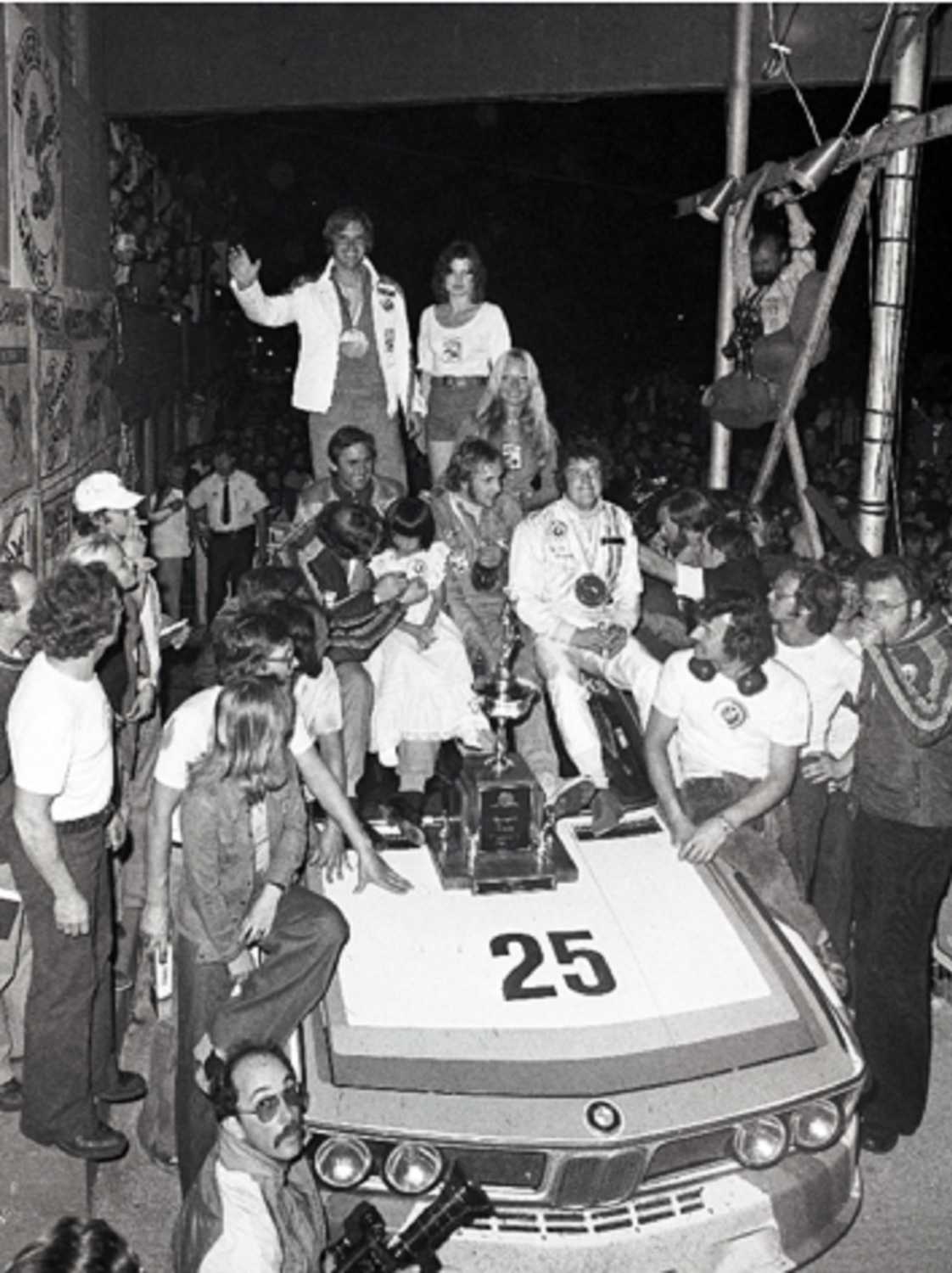

Having seen both CSLs fail to finish at Daytona, Neerpasch instructed Stuck and Posey in the #24 car to drive as fast as possible to “break the Porsches” while Redman and last-minute Petersen replacement Australian Alan Moffat drove the #25 car at a more moderate pace. It worked, and the Stuck/Posey CSL forced the retirement of the lead Porsche before its own engine expired. The #25 CSL with Redman running into the night with a failing alternator held on for the victory.

BMW Motorsport would take five wins that season, highlighted by a spectacular 1-2 finish at Riverside in the presence of BMW board chairman Eberhard von Kuenheim and sales chief Schönbeck. “Mr. von Kuenheim never came to races, but he was there because I think the day after the race was the first meeting of BMW NA,” Neerpasch recalled. “I think he was not at all a motorsport man, but once he saw the race I think he spent the whole six hours standing on a fuel drum overlooking the track.”

Full-page ads touted BMW’s achievement in US newspapers and magazines, underlined by a new tagline that proclaimed BMW “The Ultimate Driving Machine.” The 1975 IMSA GT championship fell to Porsche and Peter Gregg, but BMW Motorsport had made its mark. Finally, the public at large knew that BMW stood not for British but Bavarian Motor Works.

A more detailed look at the Sebring win and the rest of 1975 season can be seen in the documentary Go Like Schnell on Youtube: https://youtu.be/Q180dRN5QhA?si=M8ZE-Rfhq1JUI7q9

— ends—